Editorial: ‘But they struck in sympathy’

by

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

February 13, 2026

Featured in Class Dismissed: Against The State of Education (#26)

Our editorial for issue 26.

inquiry

Editorial: ‘But they struck in sympathy’

by

Notes from Below

/

Feb. 13, 2026

in

Class Dismissed: Against The State of Education

(#26)

Our editorial for issue 26.

Introduction

On 1 April 1914, the seventy-two students at Burston School in Norfolk who arrived at school that day discovered their two teachers had been sacked. After supporting the organising drives amongst the many agricultural labourers who lived in the village, Kitty and Tom Higdon had been victimised by the local landowners who controlled the school management body. In the “finest, spontaneous, and most loving act of kindness” towards their teachers, sixty-six of these students walked out in protest. Marching through the streets of this village, singing songs of rebellion, they made their way to the village green, where they refused to go back to school.

This was not a random anomaly, but a result of the teachers’ approach to schooling. As one account of the events recalled: “Children know when they are loved. They cannot pretend as grown-ups can. Had Higdon and his wife been disciples of Whackford Squeers or advocates of the ‘Big Stick’, the children would gladly have sung Tosti’s ‘Good-bye for ever,’ and good shuttance. But they struck in sympathy.”1

An alternative school with the sacked Kitty and Tom Higdon was set up on the green. Local workers raised collections to cover the fines imposed on parents whose children attended the strike school and refused to return to that assigned by the council. The “Burston Strike School” was born and would continue for over 25 years.

In this issue of Notes from Below, we focus on the education sector. Education is a sector we know well as editors. Most of us currently work in the sector. We have an array of experience working with and organising different workforces across secondary and higher education, including casualised academics, outsourced cleaners and security guards, and low-paid teaching assistants.

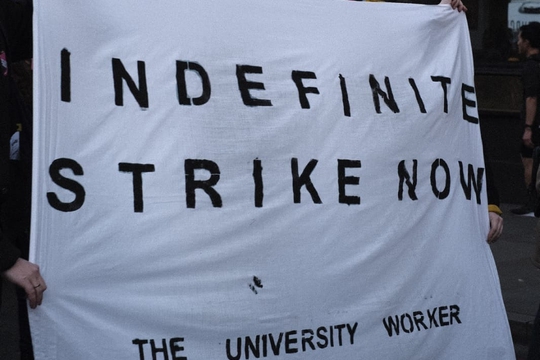

It is also a sector we have published many workers’ inquiries from before: during the pandemic we conducted a collective workers’ inquiry into the sector that formed the education chapter of our Class Composition Project; during the massive 2023 national school strikes, we helped co-ordinate the workplace bulletin ‘Marked Absent’; we have published our reflections on university struggles in our long-lasting ‘University Worker’ bulletin; and two years ago we produced a collection of worker-writing on the recent upsurge in labour organising in higher education in Britain and the US.

However, there are areas of the education sector noticeably absent from these past publications, such as nurseries, Special Educational Needs (SEN) education, adult education and support staff. These are areas most overlooked by the traditional labour movement in education, but also the areas where perhaps some of the most interesting rank-and-file organising is happening.

Across this issue, we have aimed to cover as much of the education sector as possible, from cradle to grave, enveloping the wide variety of roles that make up the sector. As well as the workers’ inquiries that make up this issue, we had also hoped to publish reflections from school students. Within the sector, they are increasingly subject to violence and authoritarianism, but also responding in kind in their own resistance and organisation, with student walkouts for the climate and Palestine, as well as organising against racism and exclusions within schools. Sadly, our attempts to produce such an inquiry within the issue’s timeframe failed to bear fruit - but we aim to make it happen in the future so that we can hear from this vital section of the education sector.

We are interested in hearing from workers in this sector, not for the sake of producing a labour movement able to win a few more pennies on the pound and better conditions for a certain strata of workers within society. We recognise the central role the sector plays within capitalism, and the political power an organised working-class within it could play in a revolutionary transformation of society. As exemplified by the rank-and-file workers writing for the ‘Disarm Education’ campaign in this issue, the self-organisation of education workers can and does have implications far beyond the schools walls - from El Fasher to Rafah, they have deep and urgent consequences.

A Brief History of Education Unions

Part of understanding our contemporary moment is understanding our history. The first trade union for teachers was formed in 1870 after a meeting of around one-hundred teachers at Kings College London. Earlier the same year, the government had passed the ‘Elementary Education Act’ after a campaign by the National Education League, who fought for primary education free from religious influence. This act set a common framework for the schooling of children, established local education authorities and provided public funding to improve the provision of schools. With teachers’ conditions now bound by a more common framework, and influenced more than ever by the state, a trade union was deemed necessary by teachers to promote their interests. The ‘National Union of Elementary Teachers’ (later shortened to NUT) was formed.2

Whilst attempts to work in partnership with the Department of Education characterised the early years of the union, its officials faced increased resistance to negotiation with union representatives as well as pressure from the rank-and-file to act on issues such as ‘payment by results’.3 This pressure eventually led to an union campaign for a national salary scale, which was won in 1919, with NUT representatives given the right to sit on the committees setting these scales. However, teachers in local authorities across the country often had to fight to have these agreements enforced, such as in Lowestoft in 1923, when over 160 teachers went on strike against the local authority for almost a year. Influenced by the nearby Burston Strike School, they set up alternative schools which educated over 1,300 children for much of the duration of the strike.4

However, frustration by various members within the union over its attitudes to various topics continued. A pressure group within the union, called the National Federation of Women Teachers, became increasingly exasperated that after many years of campaigning for the NUT to take up the policy of equal pay for teachers, no serious bargaining on this issue was being undertaken by officials with the government. They split off in 1920 to become the National Union of Women Teachers (NUWT). Peaking at 8,500 members in the mid-1920s, the union struggled to recruit a mass membership, but continued to fight, working in tandem with the broader feminist movement.5 When victory finally came in 1961, with equal pay won for teachers, the union dissolved, having achieved its mission.

Contrasting this, however, was another pressure group within the NUT formed in opposition to equal pay for women teachers. These members were expelled in 1922, forming the National Association of Schoolmasters (NAS) in the aftermath. NAS ran chauvinistic campaigns for the ‘interests’ of male teachers, including against the presence of women headmasters and for children below a certain age to be solely taught by men. They refused admittance for women all the way up until 1976, when the Sex Discrimination Act finally forced them to accept members of all genders, and they merged with their tiny sister union to form NASUWT.

In the early years of the 20th Century, university staff would join their teacher colleagues in unionising. From 1909, junior and assistant lecturers began to campaign against what they saw as low pay and poor advancement prospects. A grouping around zoology lecturer Douglas Laure at Liverpool University formed a discussion circle for junior academic staff, which slowly grew to become a campaign group encompassing other university workforces. It formally anointed itself as the Association of University Teachers (AUT) at a conference in 1919. The union was initially defined by its implicit exclusion of professorial staff, although these would soon also be integrated into the union. College and technical institution teaching staff had similarly formed the Association of Teachers in Technical Institutions (ATTI) in 1904, which would later become NATFHE, encompassing staff mostly in further education colleges and post-92 universities.

Whilst forming unions early on in the sector’s history, these unions were characterised by their professional nature, and national strikes were few and far between. Industrial workers, rightly or wrongly, were frequently less than keen to consider these staff part of the ‘labour movement’ proper, with those feelings often mirrored by education workers themselves, who could often see themselves as a class above: for instance, it took the NUT over a century to affiliate to the TUC, not joining until 1973.

As the years continued on, this situation changed. Falling working conditions and the absorption of a new generation of more militant teachers, shaped by the struggles of the 1960s, set in motion a change in pace for the sector’s workforce. In November 1969, rank-and-file members of the NUT voted down their latest pay offer, despite pleas from their union executive to accept it. What followed over the next few months was the first of a series of coordinated strikes by both the NUT and the NAS.6 Rolling strikes encompassing various different local authorities were organised, culminating in an indefinite strike of teachers in Birmingham, Southwark and Waltham Forest. Eventually, an additional £120 increase - over double what was originally proposed to the teachers - was offered by the government.7

For many teachers, the argument had been won. More militant action won results. Going forward, a more strike-prone approach was taken by the unions. The NUT gained a reputation for militancy, taking part in national and local strike action, including a London weighting strike between 1972-74, initiated by a cross-section of London NUT branches. A rank-and-file network based around the publication ‘Rank and File Teacher’ grew, encompassing up to 5,000 members at its peak in the mid-1970s.8 This rising militancy was paired in the student population, with the School Action Union formed and mass student strikes against corporal punishment in 1972.

In the same period, the ‘Cleaners Action Group’ was formed by May Hobbs, who had been blacklisted after organising her job as a nightcleaner at an art school in Cockfosters.9 Working with the women’s liberation movement, the group helped unionise cleaners across the country, with local campaigns at various educational institutes, including the University of Lancaster.10 In schools, groups of organised cleaners also emerged within NUPE, the public services union, in areas such as Somerset.11

A decade later, the women’s liberation movement also helped birth one of the largest nursery worker strikes in British history. In 1984, over 150 nursery workers employed by Islington Council began an indefinite strike against chronic understaffing, despite promises made by a new local socialist Labour administration during their election campaign to make sweeping improvements to nurseries. These workers - almost entirely young women - were motivated to organise not just by their own working conditions, but to improve the conditions of the children they cared for. Their strike would run for fifteen weeks until finally the Council yielded to their demands.

Meanwhile, teachers’ strike action peaked in the mid-1980s with two years of national strikes. However, in the same period, membership of the NUT and NASUWT fell, the former by almost a third. The proliferation of various unions in the sector meant less militant workers could decamp to other unions, such as the ATL, whilst a more hardened core remained. In the face of this fragmentation and waning public support, despite union opposition, Thatcher’s hard-right government was able to introduce a series of ‘reforms’, such as mandatory testing and a national curriculum, which weakened educator autonomy.

Throughout the decades that followed, a significant militant core of the workforce remained fighting - including the teachers who pinned Labour’s Education spokesperson David Blunkett in an office at the 1995 NUT conference after he gave an anti-union speech - with local, regional and national strikes in the sector, mostly by the NUT and then NASUWT. National strikes often consisted of singular days of action, whilst local actions tended to be longer. With the introduction of academisation by the Blair government, and accelerated after the election of the Coalition government in 2010, a series of hard fought local strikes against academisation would come to define the sector - continuing to this very day. In Lewisham and Glasgow, parents mirrored these actions with the occupations of schools and nurseries threatened with closure.

In more recent years these unions have had the tendency to merge. The AUT and NATFHE merged to form UCU in 2006, during the middle of a national assessment boycott that, combined with threats of additional strike action by thousands of cleaners and support staff, led to an increased pay offer for university workers. In 2017, the NUT and the ATL also merged to form the NEU, now the largest education union in Europe. Particularly exciting in this development was the opening up of the NEU to all workers in the education sector - meaning for the first time, an education union intended to be organised - at least in theory - along industrial rather than craft lines.

Waves of national university and further education strikes have continued since 2018, with an increasing number of local disputes - unfortunately most often around redundancies. During the same period, an increasing series of strikes by outsourced workers have taken place across universities, sometimes through more militant TUC union branches, but with grassroots ‘base unions’ such as IWGB, or even workers themselves without any union, leading the way in these struggles. These recent struggles have been widely documented by Notes from Below. Within primary and secondary education, however, only one national strike has taken place since the formation of the NEU in 2017, during the 2023 strike wave.

The role of the education system, and the workers within it, has adapted over time, but these changes have not solely been imposed from above. They have also been shaped by the workers in the sector and the struggles they have undertaken. The historic fights against sexism, casualisation and sectarianism recounted here are also not only things of the past: as various pieces in this issue show, they continue to plague us today.

Continuing efforts by the leadership of UNISON, Unite and GMB to censure NEU for organising support staff shows the scale of sectarianism that rank-and-file education workers need to challenge in the sector. This sectarianism can persist within the rank-and-file too, but often more common is a fragmentation of organised workers between unions. The day schools described by rank-and-file university workers and ‘UCORE’ network by Ellen David Friedman in this issue present two models attempting to address this situation from the bottom up.

The accounts in ‘Reflections on a Nursery Strike’ and ‘Fighting for our class’ exemplify how sexism and sexual harassment in a largely feminised sector continue to be immense issues, that have to be confronted head on if the working-class wishes to grow its power in education.

Similarly, the demands and agency of casualised workers, at the undoing of the wider labour movement, continue to often be ignored. As the pieces from workers in d/Deaf, further and higher education show, there is a strong desire from many casualised workers to organise. With effort this is not only possible, but can be transformative for our struggles.

Our task then is to understand the role of education within contemporary society, the present-day manifestations of issues that have long afflicted our movement within the sector, and how we may overcome them within and for our struggles today.

The Role of the Education Sector

Investment in education offers a key vantage point to view how a political economic system projects a vision of itself into the future. The inquiries in this issue, alongside their immediate insights into current class composition, can also be read as a bellwether for the relationship British capital intends to have with its growing crop of labour power (children and untrained adult learners). With this in mind, the declineism that runs throughout the issue should give us pause. Beyond the rhetoric, the era of “education, education, education” is not coming back. Austerity and decline is not just the industrial relations terrain of workers, but the formative experience of students moving through the British education system, from early years up to adult learners.

The role the system once played under contemporary British capitalism is changing. An evaporation of state-led industrial strategy has resulted in education becoming increasingly less influential in class stratification or the training of future workers. Understanding the function of education workers therefore requires more nuance.

Firstly, education workers’ role is to produce the skills necessary to produce the next generation of workers required by capital. This includes more basic skills, - such as literacy, numeracy and motor skills - as well as more stratified, higher level of skills to (supposedly) meet the various needs of the capitalist economy and maintain the class system. The exact ways that education further sorts and allocates students into the job market has been argued by many different educationalists, academics and political radicals. However, at a base level, education in our society aims to equip a wide array of the population with the skills necessary to continue the production of profit and reproduction of a system that allows for that.

In a mainstream education, these skills are transmitted using disciplinary authority. Forms of punishment and reward are used to repress behaviours which disrupt the aims of pedagogical instruction. As such, capitalist schooling transmits knowledge through forms of behavioural control. Therefore, even for a system that may wish to reduce the cost of reproduction of the working-class to as little as possible, it is undesirable for students to leave education without having acquired basic skills, behavioural norms and, for various strata, more specialist skills.

Secondly, it is obvious a large section of the education workforce’s jobs - notably in primary and secondary education - revolve around the management of a population legally safeguarded from work due to their age, and therefore allowing their full-time carers to attend to work. This is made clear from the particular leverage school workers hold when they go on strike: in theory, if schools can’t open, children can’t go to school, and therefore parents have to make alternative arrangements, otherwise they cannot go to work. Without schools then, and in particular nurseries and primary schools, capital would either struggle to exploit labour for profit, or the dominant culture and law around childcare would have to drastically change.13

The increased authoritarianism within contemporary educational institutions, highlighted in both ‘A Lesson in Class Struggle’ and ‘Situating the Work of Education’, draws attention to how these two roles are aligning within an austerity state. As is made clear through the various workers’ inquiries in this issue, much of the school day is now focused not on learning, but rather on ‘regulating behaviour’. This points to both a decline in the resourcing of schools by the state, as well as the wider role disciplining is seen to play in the production of the next generation of workers.

The never-ending audit culture of contemporary education, through OFSTED, Office for Students and other regulatory bodies and frameworks, has played an important role in remodelling educational quality around quantitative metrics. This has been compounded by increasing student numbers, many with complex needs, with an ever decreasing ratio of staff. Yet, in the long-term, this is also an attempt by the state to mitigate how these future workers will respond to the violence inflicted on them by the capitalist economy: ‘stop running’, ‘stop talking’, ‘if you miss class you will be sanctioned’. Whether as exploited workers, or part of the reserve army of labour whose access to reproduction is mediated through the ability to access state welfare, debt and/or ‘illegal’ activity, instilling this behaviour has value to the ruling class.

However, just because these are the roles that education plays in the capitalist organisation of society, doesn’t mean the state or capitalist class work together to do so efficiently. In many cases, these ambitions are defaced both by companies attempting to profit from education - such as outsourcing companies - and by a state ideologically committed to defunding public services. As an anonymous contributor to this issue describes the logic to various cuts in further education: “this is an approach akin to not putting oil in your car because it’s running ok so far”.

These dynamics are further complicated by the proliferation of academy chains in publicly funded education, that often seek to meet the reproductive requirements whilst also profiting from the production and sale of curriculums, lesson resources and other ‘educational’ commodities. In this sense, they are already failing to provide the basic resources needed to ensure as many students as possible leave schools with the fundamental skills they require to join the job market. Here, we see private capital in certain industries step in to boost their own agenda. In their article, Disarm Education gives the example of Barrow-in-Furness in Cumbria, home to a high concentration of arms industry jobs and where BAE employees sit on a number of governing boards, even ‘sponsoring’ certain schools, in an attempt to ensure a sufficient flow of trained, new workers into their industry.

Ironic also is how the increasing hyper-authoritarian trend in education doesn’t necessarily create more disciplined populations of new or current workers. On the contrary, in recent years, students have seemingly responded to this increasing daily repression with protests and school walkouts, including the widespread trend of “school riots” that spread through TikTok. In these, students would leave classes en masse and partake in various acts of disorderly behaviour, such as climbing up school buildings, releasing fire extinguishers, or chucking around school furniture. Whilst these ‘riots’ were presented in the media as random acts of rebellion, many were underpinned by overt expressions of discontent over particular behavioural policies. On the other hand, excessive restructures, cuts and disciplinary action seems to be the driving force for collective action by many local workforces against their employers.

If we see the building of our own Burston Strike Schools today as desirable, then these forms of resistance within the education sector must be joined up with to fight against the repressive and exploitative manoeuvrings of senior management and the State.14 This could take the form of joint struggles against repressive measures, such as the shouting that is commonly used to discipline both school workers and students. More generally, the refusal of students to be taught in a certain way could be linked up with the refusal of school workers to teach in a certain way. New, socialised forms of pedagogy could emerge from that refusal.

Education and Revolution?

So, what are we aiming for when we say that the education sector needs to change? As the articles in this issue demonstrate, education is no longer fulfilling the role historically assigned to it by the state. Increasingly, schools and universities fail to supply the capitalist economy with labour-power that meets its technical and ideological requirements. This mirrors trends across the wider public sector.

Under neoliberalism, the state and its various organs have been reorganised along market lines, on the assumption that the profit motive will render public services more efficient and effective. In practice, the marketisation of the public sector has in fact undermined the capacity of the bourgeois state to meet its basic obligation of managing capitalist growth. In education, this has meant that essential pedagogical and ideological functions are constantly frustrated by a proliferation of structural barriers. As a consequence, youth and graduate unemployment is an increasingly large part of what the education system produces.15

These crises within education are themselves bound by the long-term stagnation of the British economy. Global conditions of declining profitability paired with low state investment positions education as stuck within a self-reinforcing feedback loop of collapse; a directionless apparatus of discipline for all but those who might play a role in the sectors the state has determined as capable of growth and productivity (and so is willing to invest in). Where the state might intervene in education to help resolve more immediate labour shortages in vocational trades and services, from electricians to careworkers, a reliance on outsourced labour or overseas hiring appears preferable: both as a profitable enterprise for intermediary firms in control of hiring and employment, and in producing an hyper-exploitable class of workers who face additional challenges in organising.

In this scenario, there’s a risk of assuming that the only alternative to marketisation is an education system reintegrated into a Keynesian state. But is this really the extent of our political vision for the future of education? Are we only able to imagine transformation in terms of rebuilding the link between what education does and the needs of capital? We all want the best for our pupils and students, but we should be under no illusions about what educational success means in a capitalist society. Primarily, it equates to preparing learners for positions within a system of exploitation. In the best cases, students might come to appreciate learning for its own sake, developing intellectual autonomy and curiosity that will help them navigate this system. But even here, when education is idealised as the route to individual enlightenment, the question of education’s function in reproducing class relations is ultimately overlooked. How then to imagine a politics of schooling which confronts the role that education always already plays in class struggle?

This is a broad and demanding question, and satisfactory answers will only emerge from workers and students embedded in collective struggle within the sector. But it is a question that communists should be prepared to address, since every revolution requires an organised system of education capable of meeting its scientific, ideological, and cultural needs. For this reason, we need alternative visions of educational organisation on which to draw.

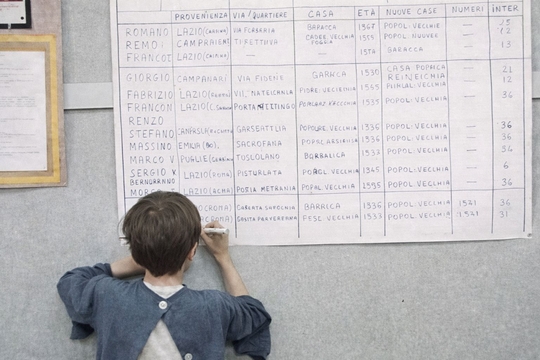

One such vision can be found in Vittorio De Seta’s 1973 mini-series Diario di un maestro (a lesser known gem of workerist cultural production). Set in the proletarian district of Tiburtino on the outskirts of Rome, the series follows a teacher, recently politicised through his experiences at university in 1970s Italy, as he takes up an entry-level post at a local school. Relegated to overseeing a class of ‘no hopes’ (sons of the region’s historic lumpen and working classes), the teacher develops an approach to engaging the young boys which is strongly marked by the politics of inquiry.

At the beginning of the second episode, the boys witness the demolition of local slums. This encounter with encroaching alien forces becomes the starting point for a collective research project into the situation of the classroom. ‘Where and how do we live?’ is the question which drives a series of inquiries into their concrete living conditions (number of rooms, number of inhabitants, number of inhabitants per room, function of rooms, public/private housing, new/old public housing etc.). With the results, the teacher explains: “This schematic we have built gives us information about this reality. Necessary information. We must try to understand why such situations exist.”

This opens up a broader investigation into the relationship between personal family history and wider socio-economic and political factors bearing on the composition of the classroom. Finally, the boys turn their attention to what’s not present in the classroom - truants working formally and informally instead of being at school. The culminating sequence shows the boys surveying their classmates in their workplaces, then mapping the results onto their already amassed research covering the classroom walls.

Diario di un maestro gives us a vision of how the school could be a site of collective knowledge production directly linked to material conditions - conditions which are inseparable from the barriers variously inhibiting the educational chances of school children. Here, delinquacy is seen not as a set of behaviors to be repressed, but as a form of intelligence responding to real conditions of life; a mode of understanding which is illegible to the traditional aims and methods of teaching. It shows how social inquiry can be a route to mobilising this subaltern intelligence for processes of collective self-understanding, self-development and ultimately self-activity.

Whether this model can short-circuit the boys’ fate is left as an open question in the final episode. But there’s an interesting counterpoint to the idea that progressive pedagogy alone can be the path to genuine educational transformation. Midway through the research project, the teacher is confronted by a colleague who points out the workload implications of his pedagogical experiment. The additional preparation and resources which have gone into transforming the classroom, entails more work for the same pay. For those with caring responsibilities, this is not an option.

Here, the underlying tension of all transformative struggles in and through education is dramatised. While education plays a key role in social reproduction, isolated instances of subverting this function ultimately run up against constraints determined by the economic organisation of the sector as a whole. As such, economic struggle led by school workers would appear to have priority over aspirations to change what education does. But a communist perspective insists that workplace struggles cannot stop at demands for better pay, conditions, or funding within the existing framework, important as these are. In the case of education, these demands must be linked to a collective challenge to the social function of schooling as a mechanism for reproducing capitalist class relations. This would inevitably face resistance from more conservative educational workers, many of whom are professionally and ideologically invested in the current organisation of education. But only when workers’ economic struggles in the sector are consciously articulated with projects that reorient education towards collective inquiry, social need, and working-class self-emancipation, can schooling become something other than a failing service to capital. In this sense, transforming education is inseparable from transforming the conditions of those who work and learn within it - and from the wider struggle to abolish the social relations that currently determine both.

-

Casey (2020) The Burston School Strike. Project Gutenberg. ↩

-

Tropp, Asher (1957) The School Teachers: the growth of the teaching profession in England and Wales from 1800 to the present day. London: Heinemann, pp. 110-112. ↩

-

This added the condition that all schools receiving government funding pass an annual inspection. ↩

-

‘100 years of unions’, TES. 20 May 2011. ↩

-

Oram, Alison (1996) Women Teachers and Feminist Politics 1900-39. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, pp. 145-146. ↩

-

Hallas, Duncan. ‘Pay revolt hits schools’, Socialist Worker, 20 November 1969. ↩

-

1969-1970 strike. Warwick Modern Records Centre. Undated. ↩

-

However, this support rapidly declined, arguably as the grip of the International Socialists, later Socialist Workers Party, tightened around the network, and it eventually folded in 1982. See: Seifert, Roger V. (1984). ‘Some Aspects of Factional Opposition: Rank and File and the National Union of Teachers 1967-82’. British Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 22(3), pp. 372–390. ↩

-

Hobbs, May (1975) Born to Struggle. Plainfield, Vermont: Daughters Inc. pp. 76-77. ↩

-

Socialist Woman Special: Lancaster Cleaners’ Campaign. July-August 1973. ↩

-

For a first-hand account of this, see Dave Chapple’s Somerset School Cleaners and their trade union, NUPE, 1973 to 1984. ↩

-

This strike is beautifully recounted by its participants in the three episode podcast series ‘Nursery Workers Bite Back’ by Childcare Voices. ↩

-

The functions schools play have also been discussed in length in ‘The Kids Are Aight: A School Workers’ Inquiry’ from issue 20 of Notes from Below. ↩

-

Another historical example of this were the students of Liceo Parini, a secondary school in Milan. During an occupation of their school building in 1968, they drew up a special edition of their school magazine, La Zanzara. As well as listing the negative conditions of student life, it also dedicated a section to the concerns of school workers, such as “the subordinate position of teachers in the educational system”. For more, see: Tarrow, Sidney (1989) Democracy and Disorder: Protest and Politics in Italy, 1965-1975. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Figures from HESA and Luminate show that between 2015 and 2025, graduate unemployment has increased by around 3%, while youth unemployment (16-24 year olds) is the highest it has been since 2011-2012. ↩

author

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The Kids Are Alright: A School Workers’ Inquiry

by

A group of school workers

/

April 24, 2024