Defending Legal Aid

by

John Nicholson

May 12, 2025

Featured in Legal Workers Inquiry (Book)

Remembering the fight against legal aid cuts

inquiry

Defending Legal Aid

by

John Nicholson

/

May 12, 2025

in

Legal Workers Inquiry

(Book)

Remembering the fight against legal aid cuts

This letter below, signed by a couple of dozen lawyers, advice workers and managers, and the Public Services and Commercial Union’s (PCS) court service branch, appeared in slightly different versions in the local Manchester Evening News and Morning Star on June 15th 2013.

The double entendre of the title – “Not Just Cuts” – was lost on them both: the Morning Star putting the heading “Legal aid attacks more than “cuts””, though – slightly amazingly for this publication – the Evening News came out fighting with “Oppose these attacks on access to justice for all.”

As the letter explained:

The defence of legal aid is not a campaign by the legal profession for the legal profession but a campaign for anyone who is concerned about justice and access to it.

Justice Minister Chris Grayling is now making the most damaging attacks on civil justice in living memory. On April 1st, legal aid for advice and representation was removed from large sections of the most vulnerable.

Citizens Advice, law centres and legal aid solicitors are now unable to offer legal aid to those needing advice and representation on debt, most immigration, housing, private family law or employment problems.

The government itself admits that 600,000 cases each year are no longer funded. This follows a 10% cut already made across the board in legal aid rates.

At the same time, the civil servants employed to administer the justice system have seen their pay frozen and their pensions attacked. The civil service union, the PCS, sees the cut in their members’ pay and pensions as the prelude to privatisation.

And the government plans further cuts in rates to legal aid lawyers, reducing the opportunities for young lawyers to go into social welfare law.

On top of these public funding cuts, advice organisations are closing or cutting their services.

This is just when people face major changes to their social rights and need advice more than ever.

The government says the cuts won’t matter much. People can just sort it out for themselves.

The top judge in this country has said this could lead to people taking the law into their own hands.

We must be clear. These aren’t just cuts.

Not only are they financial reductions in the living standards of the workers, but they are also unfair restrictions to the access to justice that makes a civilised society.

The government is heading towards a society where only those who can pay can receive services – whether legal advice, health, education or anything else.

We call on the government to stop these unjust cuts.

The letter then called on everyone to join together in a[nother] demonstration at the Civil Justice Centre in Manchester – which we did.

Further action

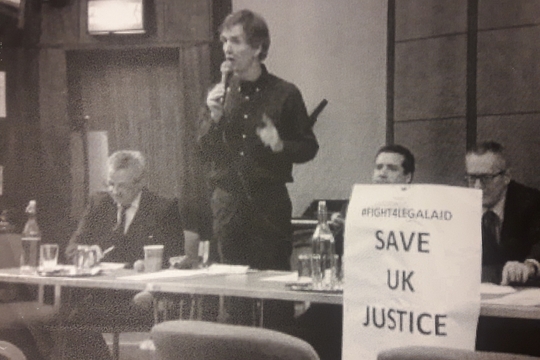

In fact, there were many demonstrations supporting legal aid in the early 2010s. On one, there were mixed feelings when the PCS union members of the court staff walked out of their workplace – because they were contracted-out G4S employees. Solidarity with the striking staff was at odds with the oppressive behaviour experienced at the hands of G4S by some of the migrants present. Another saw perhaps the largest demonstration of people in suits and ties - and some even in gowns. Lawyers demanding improvements in criminal legal aid rates were an unusual body of people for the police to be marshalling around Manchester (as my barrister colleague Mark pointed out politely to the copper on the end of our row during the march).

Legal aid lawyers, students and campaigns for justice joined together at one of the party conferences. They all used to be in Manchester, until Labour got fed up with being lobbied by Stop G4S supporters every other year and moved to the quieter streets of Liverpool. At least, that’s how it looked to us – Labour eventually dropped G4S for its conference security after the particular efforts of Jennie Formby, then Unite the Union representative on Labour’s NEC. We were joined on that occasion by Kate Green, then MP, a former respected advice worker. Though subsequently she sadly became a Zionist apologist and is now the Chief of Police in Andy Burnham’s Greater Manchester Mayoral set-up.

These demonstrations were useful in giving a focus for the dissent among both lawyers and the wider campaigns for access to justice. Gaining a wider coalition of support for legal aid is, I think, necessary, both to win the arguments in public and to create the pressure on the government that is less easy to dismiss as simply (fat-cat) lawyers wanting more money.

Looking at this more structurally, we need to start from the people who might need support. First, there has been extensive damage caused to people’s rights across the board. In reality these are all linked. They include rights to housing (see Isaac Rose’s recent excellent book – The Rentier City – which charts the trajectory of Manchester into the deep exploitation of the private landlords), employment rights (when the last Labour government repealed precisely none of the anti-trade union legislation and promises, er, to do nothing more in any next such government), benefits (where adverse media publicity affecting claimants is rivalled only by that facing migrants, and at the same time people face complicated legal regimes making it difficult to understand let alone claim correctly) and then to immigration itself (with the long and still growing list of obstructions emanating from what are basically simple racist prejudices). If these structural barriers to a fair society were to be overcome, there would be much less need for people to rely on lawyers in the first place.

There lies a conundrum. For immigration lawyers particularly, it would always be better if we were out of a job. If this were because the racist laws which we try our best to negotiate, in order to achieve a good result for individual applicants, were all repealed there would be no need for our work (a comparison between immigration legal aid lawyers and workers in arms factories springs to mind). The point is, and it extends more widely, that the context in which we work is not one of our choosing. Neither the operation of our society nor the mechanisms of our legal (and legal aid) system(s) are in the interests of the working class. Right down to the point at which we put on smarter clothing and speak as “well” as we can, trying to accommodate ourselves to the judges we are in front of, we are moving away from working with those we represent to working with those we are fighting against.

Trying to empower the people who come into law centres or other community advice organisations should surely be part of the job of lawyers who seek change. Working to overturn the iniquities in housing, benefits, and so on, is something that should be shared. It should not be “possessed” by smart lawyers who can patronisingly demonstrate their (our) expertise and impress the people they represent. So, and this is the key thing that successive governments have done to stop more widespread challenges to their cuts, privatisation and general repression, the best way to ensure that there is no future for legal aid (and legal aid lawyers) is to cut the type of organisations (and lawyers) who are providing it. No wonder they coined the “activist lawyer” label – it ought to be a badge of pride, not an insult.

Not only therefore were our campaigns of the early 2010s about the cuts in legal aid, but also about the causes of the cuts in legal aids (to coin a phrase – not). The societal effects of attacks on council housing, increased private renting, the resulting rising homelessness, plus all the anti-trade union laws, benefit cuts, and immigration restrictions, were the backdrop. The cuts in legal aid rates for lawyers were dramatic – but lawyers are still probably the second most despised profession after bankers (or have politicians now crept up the list?).

Young criminal legal aid lawyers were getting a pittance – and that was on top of the £40-50,000 university debt they were owing – and they were willing to organise to express both publicly. But it was little use to give platforms to the older (then) QCs (a senior barrister or solicitor advocate who is recognised for their excellence) who declaimed how they wouldn’t get out of bed for £250 an hour, as if this was somehow a call arousing sympathy in the public ear. Much more important were the barriers to young lawyers, even starting out in these areas of law. In social welfare law, there were decreasing jobs, low rates of remuneration, and – most of all – fewer and fewer firms (let alone law centres) existing or willing to take on these categories of legal aid work. The bureaucracy of those administering legal aid, combined with the lack (and late payment) of money at the end of it, was a clear disincentive to taking on the work in the first place. The team of immigration barristers that I worked for carried debt owed by the Legal Services Commission that was literally two years overdue.

As a result, and especially in the not-for-profit sector, the number of organisations providing immigration aid has plummeted. Greater Manchester Immigration Aid Unit (GMIAU) is a clear example – now that even Bolton Citizens Advice Bureau (CAB) (which has historically provided some immigration advice for several decades) has closed; this marks the final closure of local voluntary legal aid immigration providers in Greater Manchester other than GMIAU itself.

The government strategy (and let us presume it is a strategy) was to make things worse for people, and prevent them from being able to challenge this, by making it difficult for new lawyers to become qualified or employed. First, cut the pay for them if they do manage to become employed. Second, try to remove the organisations in which they could work to start with. We tried to bring together young lawyers and their longer-serving counterparts in legal aid work during the period of attacks on legal aid in the late 2000s/early 2010s. However, it was never going to be enough simply to have a few polite demonstrations around the law courts and their surrounding city centre streets.

That is why, during the years 2010-14, various campaigns and supporting lawyers in Manchester mostly coalesced around the defence of South Manchester Law Centre. The law centre was established in the 1970s, with local council grants. Initially called the “Manchester Law Centre” and more commonly known as “Longsight Law Centre”, for its location on the inner-city high street of this community, it was often referred to simply as “the” law centre. In those now far-off days, when there was some degree of a welfare state and functioning local government, people were able to walk into a welcoming centre who would try to work with them to overcome problems with their housing, benefits, employment and – most of all – immigration. Over the next 25 years, Greater Manchester came to boast the existence of 9 local law centres, as well as several more CABs which offered immigration advice and – crucially – the GMIAU, which still survives as effectively the only public, legal aid, voluntary organisation providing advice and representation in the whole of the north of the country. All these 9 law centres have now gone. We had to establish the Greater Manchester Law Centre (GMLC), against the grain of closures, in 2016.

Many layers of cuts and closures later – no thanks to the Blair and Brown reorganisations into their preferred method of contract culture in the late 2000s – and the law centre found itself undermined by a conspiracy of local and national government. This was coupled, sadly, with desertion by some parts of the voluntary sector that went after the remaining money that was on offer. Housing, benefits, and employment services were TUPE-d over (basic protection of employment when an organisation or service is transferred from one employer to another) to a CAB which increasingly closed local offices and hid behind telephone banks and city centre corridors. Immigration remained alone in the face of (then) 30 years of escalating racist legislation, by both governments – ever since the Labour Party manifesto of 1983 which committed the party to repealing both the Immigration Act 1971 and the Nationality Act 1981. Imagine!

Aside from the widespread community support, the campaign involved specific legal challenges to defend the centre. We took – and won – two judicial reviews in Manchester; one against the government over the awful Labour-created Legal Services Commission (LSC), who should have been defending legal aid but instead were cutting it – and its practitioners – to ribbons. The second was against the Labour Council in Manchester who should have been defending their last remaining law centre, but instead had been engaged in making deals with other voluntary sector advice agencies – notably the CAB – to end South Manchester Law Centre for good. We were lawyers and we were representing lawyers. But we were overtly campaigning, with the support of all the community groups and individuals with whom the law centre had worked for the previous three decades.

On national TV, including the BBC’s One Show, whose anodyne presenters looked totally bemused after the piece had concluded; politics rarely intruded into their arena. Amusingly, when the reporter was describing people seeking asylum, who the law centre represented, the camera cut to a black man shuffling down the pavement opposite in a dowdy raincoat. This was in fact George, who was one of our barristers from my former chambers.

The courtroom was packed on both occasions. We were joined by local actor Julie Hesmondalgh. The judge in 2010 gave us a hard time – and occasionally in response to one of his questions, I would look sideways to my barrister colleague Mark, who looked down the line to our other colleague George, and then on to Sukhdeep (the law centre co-ordinator), while Craig (at the time a law centre volunteer, now an excellent immigration barrister in his own right) ruefully shook his head behind us. The LSC had hired a QC. My colleagues found this out at the start and slightly panicked. I thought it more appropriate to go up to him and ask him what on earth he was fighting this case for. By teatime, this QC wanted to get on to some of the more abstract of his submissions – and the judge stopped him in his tracks (the judge wanted to catch the train back south). Allowing permission for us to claim judicial review, the judge acknowledged that he might have been a bit hard on us – his eyes flicked in my direction. The QC was gutted (Though not that gutted. Freedom of Information requests confirmed later the £47,000 that the LSC paid out in his direction to try to close down the law centre).

Unfortunately, the full judicial review hearing, for which we had got permission at the hearing in Manchester, never happened. There is another moral, or two, to learn here. After the permission hearing, the judge was keen to get the full hearing to take place quickly. He feared, perhaps wrongly, that the law centre would collapse if it was not given some certainty and quickly. Alternatively, it is possible that the effect of the challenge on the LSC’s new rules for legal aid contracts would have been that they would have to rewrite them all, and retrospectively, as other organisations had by then been given greater favour at the expense of those such as the law centre (and the GMIAU).

Our team was panicking. We would not be ready. We could not be. There was one dissident opinion – if we are not ready, think how much less ready the other side will be. Probably we should have grasped the nettle we were being offered. Because we did not do so, a bad judge (now promoted still higher) in a court in London heard a bad case (that is, a case on the same issue but with very weak facts) and ruled that the LSC contract arrangements were not irrational. The effect of this was that we would almost certainly now not succeed in our full claim. Sukhdeep worked all over the Christmas break to get the best settlement he could. The law centre survived and we had had a notable victory. But the underlying financial weakness – and the LSC nonsense – remained.

Two years later, and another attack on the law centre, this time by the Council, who were finally getting around to cutting all the money they had previously given the centre. The court was packed, inside and out. Applause broke out at appropriate times during the hearing. This raises another point – barristers are required to appear not to encourage unruly behaviour by the audience in the court; and it possibly is a mistake if there is too much noise too often. We said to our key supporters that, at the right moment, they should clap. Like the very presence in court of lots of people, it has an effect.

Two council officials attended the hearing and sat like muffins on a griddle. George conducted the hearing for our side, brilliantly. At one point, when the judge referred to a “very good letter written by the law centre”, he looked sideways at me, I looked down the line, and we ended up all looking at Sukhdeep in disbelief. He had written a “very good” letter?!

Again, we won. Again, there was a settlement afterwards. The law centre struggled on for another two years before, perhaps inevitably, there just wasn’t the energy left to keep balancing the books – or to pick another fight with local and/or national government. What follows is the story of the start of the “new” law centre – GMLC – arising out of the ashes, with the slogan ‘Fighting Together for Free Access to Justice’ – and meaning it. For now, the thing is that we had not given in, we had fought – for four long years, and we had won. With community support, crowded court rooms, political commitment as well as legal skills, it is possible to be successful. Equally, it is necessary to re-emphasise that the judicial reviews were part of the campaign, not the end in themselves.

While on the one hand, the legal defence of South Manchester Law Centre was a legal issue, it was also a part of wider campaigns at the time, to defend legal aid and to oppose the closure of advice services generally. Manchester Council did not only pick on the law centre, it shut up shop on its own, the well-regarded and independent Manchester Advice Centre. Young lawyers and others were campaigning together to stop the legal aid cuts that the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act had ushered in, in 2012. The Access to Advice campaign held several national conferences in Manchester and fringe meetings at the Labour Party conference here. The Shadow spokesperson for legal aid in the House of Lords, Willy Bach, was involved in at least one of these – he went on to become a Patron of GMLC. He notably improved what he was saying as a result of being given more freedom to do so by the election of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader (and perhaps by the Premier League title which was gained by his own Leicester City in 2016…)

Immigration barristers suffered the loss of hourly rates, to be replaced by fixed fees, followed by cuts in the fixed rates and in travel expenses.

Further restrictions came in the shape of what amounted to conditional funding – if we didn’t get permission for appeals to the Upper Tribunal, we wouldn’t get paid. Yet as I have argued all through the campaigns, especially by lawyers for lawyers, you cannot tell the public that the profession isn’t well paid. Lawyers are the second most unpopular profession after bankers. The issue must be about access to legal aid, for those who cannot afford to pay a lawyer and cannot find one locally because the organisations have been put out of business by the very legal aid system which is supposed to defend them. Greater Manchester Immigration Aid Unit, for example, brilliantly managed by Denise out of a financial (and arguably political) hole when she arrived, as I’ve written, is effectively the only not-for-profit immigration legal aid provider, not just in the county of Greater Manchester, and (pretty much) not just in the north-west region, but almost in the whole of the country north of London. Its national reputation, for casework and for policy development and publicity, is deserved. But its isolation is a symptom of disaster.

The Home Office may have been broken but the infrastructure of legal support for its victims has been savaged far worse.

For all the above, that was why we “had to do something” – why and how the Greater Manchester Law Centre came about. That’s maybe a story for another day.

And, as the top judge said back in 2013; “[these cuts in legal aid] could lead to people taking the law into their own hands.

Featured in Legal Workers Inquiry (Book)

author

John Nicholson

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next